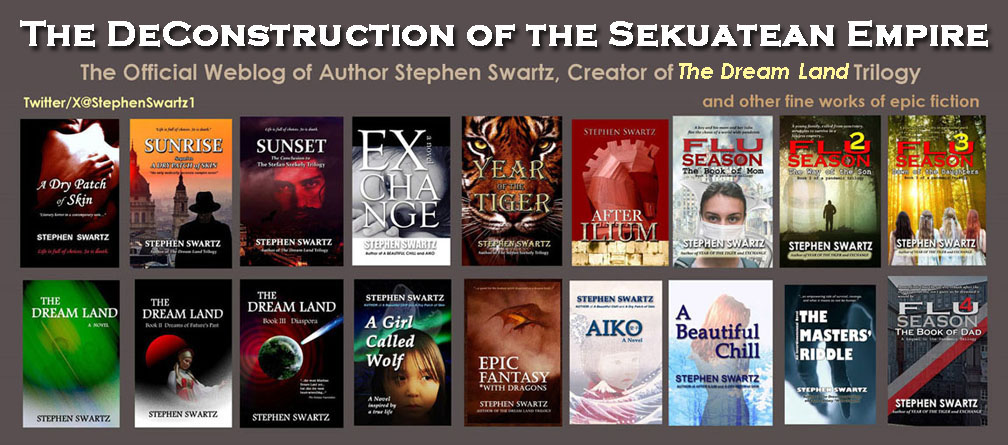

FLU SEASON - a pandemic novel, part 3

As I prepare my latest novel for publication, I consider each revision pass with different eyes. In fact, I'm forced to see each scene and the characters in it in a new light. Partly this is simply the product of an additional reading. It is also an opportunity to revisit an invention and reflect on where and how the parts of that invention originated.

I'm talking about the characters who inhabit this story of a teenage son and his mom (and her tuba) and their escape from a pandemic-ravaged city for what they hope will be relative safety in the country. I can sit back and know where I got bits of each character. The son is not based on me, however, and the mother is not in any way based on my mother. They are composites: part of this person I knew and part of that person I know. Other characters begin as stock figures, perhaps, but as their role in the story expands, they take on other traits borrowed from...wait for it: people I have known.

A common aphorism for writers is "write what you know". That may end up as an autobiography, or turned into a work of fiction by changing the names. Many writers' first novels are thinly veiled autobiographies, we understand. I think the idea is to write about things I know from direct experience. I may be an expert on those experiences, of course, but how can I say that people want to read about my exact episodes? Sure, we believe anything can be interesting if written in an interesting way...but really? You want to read about my tuba lessons? Don't worry, I can embellish them to make them fun to read. I'll admit it is a lot easier to write about something (or use it in a work of fiction) if I have experienced it myself. But a good novel needs more and that requires borrowing, inventing, or straight-up guessing (if access to research isn't available). But that could get a writer in trouble.

If we do not write about only what we know directly, we could be accused of borrowing (or "appropriating" in certain contexts) details we may include in a work of fiction. There are many easy examples. How can a male writer write a female character? is a common question, less so the reverse about how a female writer can write a male character. Usually I can answer both questions thus: writers are professional observers. We observe, describe, borrow from people we have known. The same goes for writing characters of different races or ethnicities from the writer. Or any of a number of categories like these. In most cases, I don't think the writer is trying to portray a different character in a deliberately offensive way, though it may result in such. Rather, the writer gives the best effort possible in depicting the character realistically within the context of the story.

So what we have as a bottom line is the writer is either writing from direct experience or writing as a phony. Let me suggest another answer: the writer is an actor, and inhabits each character as needed, essentially becoming that character for the purpose of acting in a given scene. I can understand that not all writers welcome this schizophrenia - recognizing the mental health condition as a serious malady and not to be used jokingly, of course. My usage of the term is merely to suggest the multiple personalities a writer may operate within in order to create believable and compelling characters. We want readers to welcome a character, no matter how close that character may or may not be to the author's true self.

If readers wonder how I know how this or that character would think, well, I'm imagining, certainly, but not absent any knowledge or experience. For example, the teenage girl character in the novel is based on the appearance and personality of a girl I knew in high school. The mother character has the spunkiness of the mother of a friend of mine during my high school years. Some of the townsfolk in the second half of the novel are based on people I have known, borrowing both their appearance and their way of speaking - which reflects their way of thinking. The story the vagabond in the pine forest tells our protagonists is actually my own experience with the virus. And the teenage son, although not based on me, I have let borrow some things from me and my experiences: for example, the tales of the Schnauzer and the bunny, as well as his Asperger's traits. Another 'borrowing' is when one character tries to set up their new society based on the society portrayed in a famous novel.

A good writer is a good actor, let us agree. Then comes the translation of the acting into words on a page. The story telling then the story writing. The idea then the craft. But it is all made easier when it's the same person doing all of it. I often feel lucky in having my particular set of quirks, which both entertain myself as well as, I hope, those who read what I put together as novels. Thank you for your continuing support; it makes the acting worthwhile.

UPDATE: The revision stage has come to an end and the cover art is starting. Publication is expected in mid- to late summer. Next post, I'll break down some of the events in the novel.

(C) Copyright 2010-2022 by Stephen M. Swartz. All Rights Reserved. No part of this blog, whether text or image, may be used without me giving you written permission, except for brief excerpts that are accompanied by a link to this entire blog.

Violators shall be written into novels as characters who are killed off. Serious violators shall be identified and dealt with according to the laws of the United States of America.