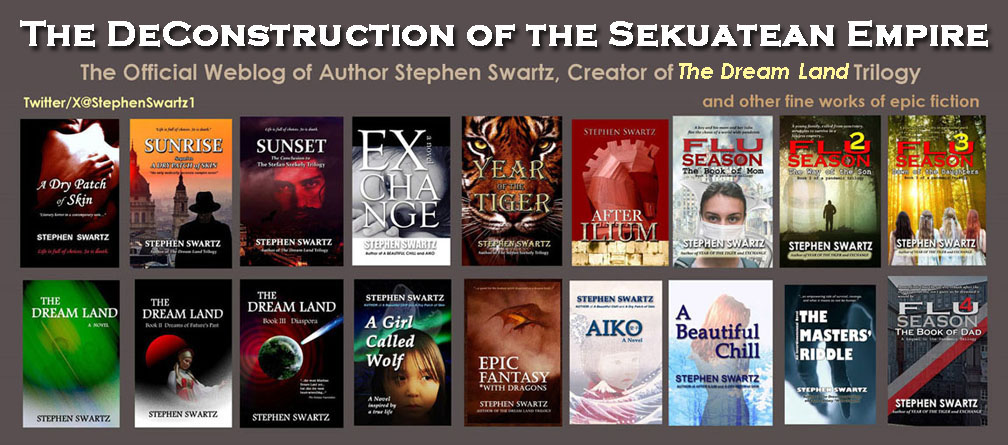

I hope you had a lovely holiday period and are rested and ready for all the new year has in store for you. As for me, I continue dabbling at yet another novel in my FLU SEASON series, revising Book 4 and starting Book 5.

However, for those of you who may only know me as a writer of dubious fiction, in my previous life I was actually deep into music and known as a tuba player and composer. A strange set of circumstances indeed! I was reminded of that recently with the Netflix film MAESTRO, concerning the life of Leonard Bernstein. This blog post is not so much a review of that film, which I enjoyed very much, but the odd connections seeing this film brought back to me of my previous life.

At the Conservatory, I studied music theory and the related courses which had me composing more music. My instrument there was the tuba, which I had been playing since junior high school after starting on French horn at age 7 before switching. I was the principal tubist in the wind ensemble, the only tuba player in the orchestra. As part of my education, I learned to play several other instruments, including harp, mostly so I would know how to write music for them. Later, when I transferred to my parents' alma mater for my final two years, I also played in brass ensembles and had my music played in different situations and performed in concert. It was a big thrill for me but I knew I was not up to the standards of the composers I admired.

So I eagerly anticipated the film and was pleased when I first watched it. It was not so much a documentary of his career but more a study of his relationship with his wife and their children during his career. This presented much that I hadn't known or considered wanting to know previously. Throughout the film excerpts of Bernstein's music filled the soundtrack, as appropriate. I didn't recognize many of them. One that caught my attention was the scene where Bernstein is sitting at his piano composing a new work. We hear the music as we see a close up of his pencil drawing notes and lyrics on the score paper set on the piano, an experience I, too, had often done in my youth. The music we hear is from his composition Mass, a re-envisioning of the traditional Latin mass. That music caused me to recall that I, too, had written a mass and I rushed to the nostalgia trunks in the basement to dig it up.

Not to toot my own horn, but... I scribbled out what I called a mass on green score paper, marking off the sections of instruments and chorus, using the traditional text. I was not a religious person wanting to create a mass so much as a composer who found inspiration in other masses, particularly by Berlioz, Mozart, and a few others. I recalled I had titled my mass the "Brass Mass" because it began with a magnificent brass fanfare. I got obsessed with finding it and twice I pulled out music I thought was it only to find as I read through it that it was not the Brass Mass but something else. Eventually, I concluded that "Brass Mass" was only my nickname and not the true title written at the top. At any rate, there it was: most of a mass, ready to be copied neatly from my scribblings! Oh, but that was long ago and far from where I am today as a scribbler of novels.

From the movie, I had to look for my CDs of Bernstein music. I opened the first of several boxes which I knew contained my collection of CDs and there - right on top - was the double CD box of Bernstein's three symphonies. It seemed to be an omen. Of course, I listened to them once more. I followed the scores on YouTube. I watched performances on YouTube with Bernstein conducting. I ordered a CD of Mass and went through it several times. I became a little obsessed with my music career that had been put away for so many decades as I switched to English and became a professor of English instead of Music. I feel a little sad that I made that turn, but it seems now is too late to dive back into that pool and hope to swim again. I still have that trunk full of music manuscripts, most of them never played even in a read-through session. I include here a few excerpts as a kind of proof.

From the movie, I had to look for my CDs of Bernstein music. I opened the first of several boxes which I knew contained my collection of CDs and there - right on top - was the double CD box of Bernstein's three symphonies. It seemed to be an omen. Of course, I listened to them once more. I followed the scores on YouTube. I watched performances on YouTube with Bernstein conducting. I ordered a CD of Mass and went through it several times. I became a little obsessed with my music career that had been put away for so many decades as I switched to English and became a professor of English instead of Music. I feel a little sad that I made that turn, but it seems now is too late to dive back into that pool and hope to swim again. I still have that trunk full of music manuscripts, most of them never played even in a read-through session. I include here a few excerpts as a kind of proof.

"Only the Music Moved" was a composition class assignment: we had to set the text to music. This is my version. You are welcome to play it, perform it, and enjoy it.

But, alas, in Kansas City there were few opportunities I knew of or was willing to pursue. I expected them to open for me, to be invited in, rather than working hard and making connections, schmoozing and galavanting to get a project green-lighted. I was rather shy in those days, although I meant well and had, by my own admission, good ideas. C'est la vie! I had my chance. Nevertheless, I did succeed in my new career: switching to English, writing stories instead of music (but always using music to inspire stories), and when the publishing world evolved past sending a box of paper around to offices hoping someone might read them and make me famous, well, I happened to get something published. That began a new career for me.

Now my eighteenth novel is soon to be available (part of the FLU SEASON series) and, for what it may be worth, I am happy just to complete it to my satisfaction and make it available to readers. The rest, the remaining steps of the process, is up to readers. I could have written music to make myself happy, and shared it with those who might also enjoy it. But I learned early on how much trouble it was to copy out the parts for an orchestra work versus typing a single copy of a novel manuscript then taking it to Kinko's for additional copies to send out. I'm reminded of a 66-page single-spaced novelette I typed out during high school that I offered to a friend who passed it to another friend who passed it on around the school. Everyone loved it (a rip-off of 1984). I doubt that a piece of music would have been heard by as many fellow students as that stapled manuscript was read. Such is life. The experiences we have somehow inform other experiences and we reach a point where we see those connections and life makes sense.

---------------------------------------------------------------------

(C) Copyright 2010-2023 by Stephen M. Swartz. All Rights Reserved. No part of this blog, whether text or image, may be used without me giving you written permission, except for brief excerpts that are accompanied by a link to this entire blog. Violators shall be written into novels as characters who are killed off. Serious violators shall be identified and dealt with according to the laws of the United States of America.