Even after shifting to an online version of teaching to finish the spring semester, I still had big plans for summer travel. Then, week after week, I kept putting off hitting the road. Until the summer had waned and I was back to the same ol' same ol'. So, instead of driving to parts unknown, I stayed home.

Staying home is not a great hardship for me. It's what I do whenever I do anything. I can easily occupy myself with the usual writing and editing, along with reading and some movies on DVD. At first, I thought I would start a new novel, something apocalyptic - obviously. I got a good start but the idea ran dry. I started reading other apocalyptic books to get inspiration. Good books, but it didn't work.

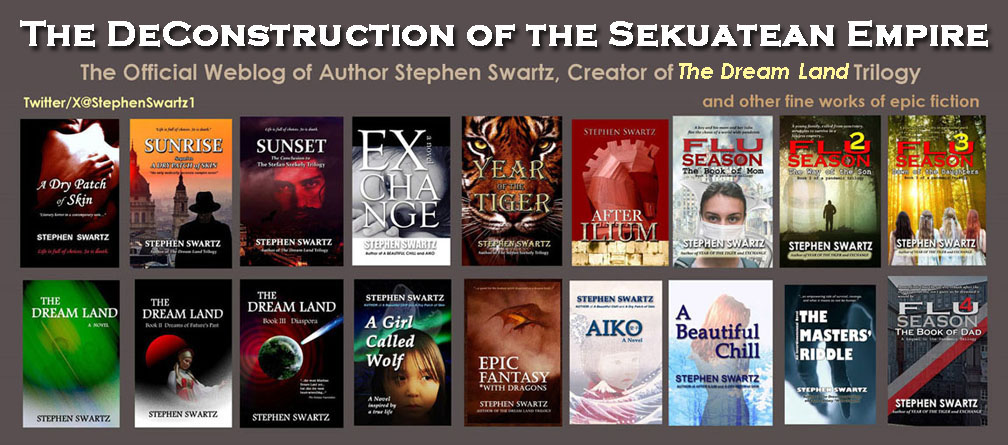

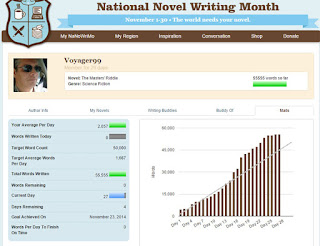

Next I thought I should use my time to finish some unfinished manuscripts. I settled on a sci-fi story I had started in a National Novel Writing Month competition a few years past. I even made a tentative book cover for it. As expected, I "won" by hitting the 50,000-word threshold, then I got distracted with other projects and left it unfinished. I always intended to finish it but I left it at a crucial point where I realized how off track I had gotten. But first, before I returned to the novel I had titled THE MASTERS' RIDDLE, I told myself I should work on one more revision of my already finished manuscript of an action-adventure magical realism novel titled YEAR OF THE TIGER, which will be coming out this fall.

All right, done. I completely revised, edited, and formatted that ancient manuscript and polished it to within an inch of its life. It is now ready to go.

So...back to the sci-fi book about the little alien who is captured by mean invaders and just wants to go home....

I always liked the idea but writing it was taking too much of my soul. The protagonist was, after all, a non-human character, forcing me to think way outside of boxes. That was a fun aspect of writing the story, of course, but challenging. As a professional linguist, I love playing with languages and alternate ways of thinking. And world building? Don't get me started! But by the time NaNoWriMo ended, my alien had slowly shifted into a regular human. Sure, I was hurrying to finish the competition; I knew I could revise it later, but the way that portion turned out left me puzzled about how to shift it all back on track.

So there I was with a whole summer and nothing to do, nowhere to go. I did try to work on it more than a year before. I had gotten a great new idea and just started in with a whole new scene. That was interesting and it worked. I would make the two storylines dovetail. But I got distracted again by other projects. So now, in 2020, I thought I might as well work on it. So I picked it up where I had left off with the new section from a year ago - where my protagonist is back to being a little alien. (I knew I would work on the original "left off" section and make it fit the new section later.)

With a rough outline from previous planning - which is odd, because I don't usually plan and I don't usually outline, at least not more than what happens in the next scene, or this section will go from here to there - I headed on from what would be the exact middle of the story. It was like going to see a play and in the middle of Act II, the whole cast changes costumes and starts forgetting their lines, and the director just stops and tells the audience to come back next year and it will all be fixed. You return and pick up the play in Act III and everything seems fine for Act III but you wonder what happened in Act II the year before. Anyway, I was willing to proceed with Act III and write it all out to the end. Then I would go back and fix the section where my alien hero slipped into being a human.

So I did it. Just finished it. The ending that happened turned out to be a very satisfying conclusion although not the one I had originally planned. How we get to that conclusion also had some twists I had not imagined originally. Happy little coincidences. But all the more powerful - I mean visceral. I think it is a "happy" ending in some ways but raises disturbing questions, too. I like those kind of stories.

Anyhoo...our alien hero struggles to get home, but how do you get home when home is another planet far, far away? Even if you get help from other kinds of creatures that have escaped... Even if you form an army to fight against your captors... Even if you find and capture the machine that enables your captors to go through an interdimensional portal to other worlds and kidnap creatures for slave labor or experiments... how do you get home? And what will you find when (or if) you do get home? Totally depressing possibilities make for a great story.

At least you have the cast of other alien beings from several different worlds, speaking different languages, having different cultures. Could there be any story with more diversity? So I got to invent different species, each with its own way of doing things in their normal lives on their home worlds, with different languages, and so on. World building! That was fun. Easy enough to describe beings from tropical worlds, desert worlds, frozen worlds, watery worlds, and so on. How they are mostly "upright" and mostly "intelligent" is solely because those are the kind of creatures the invaders choose to bring back as captives.

Languages and how they communicate was both the most frustrating aspect and had the most clever solution. IMHO. They speak (verbal utterance) in their own language, of course, but some have telepathic ability. Others are intelligent enough to convert the symbol patterns of one language into the patterns of their own language and thus understand. Some creatures pass pure ideas to other creatures without the idea needing to be coded into a language system. And so on. The hardest part was deciding how to show each different kind of communication on the page.

All right, enough teaser! I will save the big twists for another blog post sometime in my fallcation. In the meantime, look for my action-adventure novel of manly daring-do where a man-eating tiger with vengeance on its mind takes on a crazy cadre of inept hunters (warning: not a comedy) in YEAR OF THE TIGER.

[Note: This is my first blog post using the new design of Blogger. It is what it is.]

(C) Copyright 2010-2020 by Stephen M. Swartz. All Rights Reserved. No part of this blog, whether text or image, may be used without me giving you written permission, except for brief excerpts that are accompanied by a link to this entire blog.

Violators shall be written into novels as characters who are killed off. Serious violators shall be identified and dealt with according to the laws of the United States of America.