Dear Students of Writing,

I love you all. Really, I do. It is a pleasure for me to spend a short time with you each class, assisting you in developing your writing skills and encouraging you to consider writing as an important facet of your adult lives and whatever careers you may undertake upon your graduation.

To that goal, let me provide you with a short list of problems I constantly encounter and examples that will show you how to avoid those problems. Granted, there are many issues we struggle with in each and every paper, but this short list consists of the problems I find most often semester after semester.

To that goal, let me provide you with a short list of problems I constantly encounter and examples that will show you how to avoid those problems. Granted, there are many issues we struggle with in each and every paper, but this short list consists of the problems I find most often semester after semester.

Therefore, I shall expect to never find another example of these particular errors in your subsequent writing. That's a fair deal, is it not?

Little

Notes on Little Errors

comma splice sentences

The comma-splice sentence is where two or more complete

sentences are joined by a comma. To correct the problem, try one of these

solutions:

1) replace the comma with a period followed by the start

of a new sentence

2) replace the comma with the word and

3) make the comma into a semicolon

Example:

I went to school in Philadelphia, it

was the best year of my life.

You can rewrite the sentence one of these ways:

I went to school in Philadelphia. It

was the best year of my life.

I went to school in Philadelphia and it

was the best year of my life.

I went to school in Philadelphia; it

was the best year of my life.

(Remember to check the rules of semicolon use below!)

me and my sister / my sister

and I

We like to be polite and put others before ourselves,

yet this can be confusing when we write the same phrases as subject versus as

object.

For example:

Me and my sister went to the mall.

Should be: My sister and I went to the

mall. [as subject]

They are the best friends of me and my sister.

OR

They are the best friends of my sister and I.

Should be: They are the best friends of my sister and

me.

To check the correctness of the phrase, try leaving out

the my sister and just use I or me and see how it sounds.

Then add back the my sister part.

there / their

It's easy to remember the difference! Think of the I

in THEIR as meaning a person! THEIR is a possessive pronoun. THERE

designates a place or state of being. For example:

I like riding in their car. Their

car is parked over there.

There is nothing better than driving their

car!

to / too / two

These words are often confused and spellcheckers won't

catch them! For example:

He is good at Math. She is good at Math, too.

[also]

The two books we bought were too

expensive! [number and high amount]

We are going to school to take a class in

biology. [direction and as auxiliary verb]

proper nouns / nouns

We capitalize the names of people, places, and

organizations. However, we do not capitalize the noun when we leave off

the particular designating word. For example:

I graduated from Northeast High

School.

(Northeast is the name of the high school so we

capitalize the entire name.)

I graduated from high school last year.

(high school is not the name of the school, just what

kind of school it is.)

Don't forget: we graduate FROM high school, not graduate high school.

Schools do not graduate, only students do.

everyday vs. every day

Everyday is an adjective

while every day is an adverb and a noun.

This is my everyday pair

of shoes.

Every day I wear the same

pair of shoes.

people / things &

conjunctions

We like to give people credit for being human so we use who

as a conjunction and reserve that for use with things. For

example:

The people who came to school were the happiest.

Cars that crash never work as well as they

should.

if / whether

We generally use if in situations where the

answer is yes or no.

We use whether when we are comparing things that

have relatively equal value.

I want to know if students use "if" too

much in their papers.

(The answer is:

"Yes, they do.")

I want to know whether students prefer history

class or English class.

(The answer is:

"They prefer English class.")

amount / number

When something can be counted, such as people, we use number.

When something is uncountable, such as water (but not

glasses of water), we use amount.

The number of people surveyed was one hundred.

The amount of beer we drank was more than we

could afford.

then / than

Remember that the word then refers to

1) a

sequence in time, or

2) a cause and effect relationship.

The word than

refers to a comparison being made.

We stayed at school until five o'clock. Then

we went home.

I'd rather study than watch television tonight.

nice

Originally from the Latin word necius

meaning "ignorant, not knowing"

Old French = simpleminded, stupid

Middle English = foolish, wanton

Modern usage = 1. marked by conformity to convention; not unusual

2. pleasant and satisfying

Try to use a more precise word!

OK

Originates from the Democratic

O.K. Club of New York City.

In the 1840 Democratic Party campaign, Martin van Buren, who was born in Kinderhook, NY (near Albany), was the

candidate. Martin van Buren was affectionately called “Old Kinderhook”

and the designation “O.K.” was a secret sign of being a member of the O.K.

Club; hence, an accepted person. (You can hold up your hand in an

"OK" sign or gesture, touching the tip of the index finger to the tip

of the thumb in a loop with the other fingers extended, and it looks like the letters

"OK".)

Proper usage is to write it as: O.K.

or o.k.

(Writing it without periods is OK,

too, but keep the letters as capitals, in that case.)

okay = spelling of the

pronunciation of the abbreviation (used it only in dialogue)

all right

The correct form is: Is everything

all right? NOT Is everything alright?

(Exception: in story dialogue,

characters sometimes say: “awright.”)

i.e.

id est (Latin) = that is

(“in other words”); used to introduce a rephrasing of the primary statement

I have a great respect for

her, i.e., I’m impressed by her success.

e.g.

exempli gratis (Latin) =

example for free (“for example”); used to introduce a series of examples relevant

to the primary statement

She played only team sports

in college, e.g., softball, soccer, basketball.

etc.

et cetera (Latin) = and

similar; used to indicate the previous pattern or item continues in a similar

fashion. (Note: There is no need to use and with etc. because and is included in the

abbreviation etc.)

She played only team sports

in high school: softball, soccer, etc.

possessives & plurals

possessive: It's a student’s book. (it’s = it is [conjunction])

plural: Many students have books. (all the students)

plural-possessive: The students’ books are expensive. (more than one student)

:

(colon)

A:B —used to:

1) list

examples originating in statement A,

2) answer a question posed in statement A;

statement B is not a complete sentence

1. I like fruit: apples, pears,

and oranges.

or

These are the fruit I like: apples, pears, and oranges.

2. Film versions have captured the

horror of the monster [how?]: he talks!

;

(semi-colon)

A;B —used to:

1)

rephrase statement A for a particular effect,

2) connect related statements

closer than as consecutive sentences (complementary statements); statement B must

be a complete sentence

1. He is the best chef in town;

he’s been given many awards.

2. They enjoy dining out at

expensive establishments; the thrill of walking out without paying is greater

at such restaurants.

’

(apostrophe)

Do NOT use for plural forms

of acronyms and years; using the apostrophe in such cases makes the acronym or

year possessive.

CEOs (not

CEO’s) CDs (not

CD’s)

1980s (not

1980’s) 1980s

= 1980 through 1989

1980’s = only related to the year 1980

however

Always use commas with the word

“however”!

However, we won’t be showing the

whole film tonight.

We won’t, however, be showing the

whole film tonight.

We won’t be showing the whole

film tonight, however.

[Exception: however as a descriptive term, for example: It will be good however he plans it. = no matter in what way he plans it.]

double negative

As in math, two negatives result

in a positive; the same is true in English (but not always in other languages).

We don’t have no more bananas.

We don’t have any more

bananas.

redundancy

No need to use a qualifier when

the quality is obvious: large in size, blue in color, fast

in speed.

money & time

$12.75 = twelve dollars and seventy-five

cents

$12.00 = twelve dollars and no

cents X (no need to use cents if 00)

$12

= twelve dollars

10:30 am = ten-thirty

10:00 am = ten o’clock X (no

need to use minutes if they are 00)

10

am = ten o’clock

generic “you” & he/she/they

Do not use “you” in academic

writing unless you are directly addressing the reader! If “you” refers to

a generic person, use alternate words.

First, you have to go to

registration to get your schedule.

First, one has to go to

registration to get one’s schedule.

If possible, try using a

plural form such as “students” or “people.”

When a student parks

on campus they must have a tag on their car.

When students park on

campus they must have tags on their cars.

Use “he” and “she” when

appropriate but be aware of the awkward effect when the words are

compounded. Or try using a plural noun.

When he or she takes the

final exam, he or she must bring a blue book.

When he/she takes the

final exam, he/she must bring a blue book.

When students take the final

exam, he or she must bring a blue book.

When students take the

final exam, they must bring a blue book.

Use “he” or “she” when

referring to a same-sex group.

Sisters in my sorority must

always have their pledge card with them.

A sister in my sorority must

always have her pledge card with her.

numbers

Write out numbers which would be a

single word (one hyphen is allowed).

It’s one in a

million. NOT

It’s 1 in 1,000,000. NOT

It’s one in 1 million.

There are 25 of

us.

NOT twenty-five

He was born in

1978. NOT

nineteen-hundred seventy-eight

[Exception #1: In a research paper

it is better to use all digits/numerals in paragraphs where you are writing a

lot of statistics.]

Combinations of numbers and words

are permitted:

The budget this year is 1.5

million dollars.

OR

The budget this year is $1.5

million.

[Exception #2: When characters say

numbers in dialogue (but not when quoting someone in a research paper)

the number is written out no matter how long the words may be. Same applies to

abbreviations, like Dr., Mr., and Mrs.]

As I counted the 25 dollars in my hand, I called to Dr. Smith: “Doctor

Smith! I’ll be there at seven-thirty with twenty-five dollars!”

streamlining

Never use two words when one good

word will do.

We spent the class talking

about poetry.

We spent the class discussing

poetry.

That game show is kind of like

my Ethics class.

That game show is similar to

my Ethics class.

Never use a colloquialism when a

standard word is available.

Nowadays, people can fly

there in two hours.

Today, people can fly

there in two hours.

Oftentimes, we get a

cappuccino after class.

Often, we get a cappuccino

after class.

commas & lists

Though it is not incorrect, it is

better for the sake of clarity to use a comma before “and” when listing items.

We went to Kansas

City, St. Louis, and Chicago.

quotation marks

“

”

‘

’

In American English, double

quotation marks are the primary marks and single quotation marks are used when

necessary within the double quotation marks.

Periods and commas always go

inside the quotation marks, no matter whether it is a quotation or a word

marked for emphasis.

Question marks that occur within a

quotation remain inside the quotation marks; otherwise, question marks (as well

as colons, semi-colons, dashes, and exclamation points) go outside of the

quotation marks.

Quotation marks are also used:

1)

to indicate a word is used as the word itself and not as part of the sentence;

2) to emphasize a word or phrase for its satirical nature or its unusual usage;

3) to mark the title of an essay, story, article, or song; or

4) to mark a

phrase as a common expression.

Some examples:

Mr. Smith said, “Jones told us Bob’s ‘got a fine head on

his shoulders.’”

Mrs. Brown told Henry to get his “newfangled contraption”

out of the way.

“There’s no excuse for not knowing,” cried his father.

“Is there any of that pie left?” he asked.

In his essay “What’s Wrong With Interjections?”, Peter

Jones responds candidly: “Balderdash!”

His colleagues insisted that he retract his ‘claims,’ the

journal reported.

Isn’t “quotation” a better word to use than “quote”?

“Quotation marks” are what this punctuation is correctly

called.

His actions show him to be a “boy who cried wolf”!

The contract was unreadable, full of errors and

“doublespeak.”

PLEASE NOTE that the above notes are intended for academic writing in particular and everyday writing in general.

Writing fiction or poetry or something of a creative nature will entitle you to break some or all of the above "rules" if done so in order to achieve a particular rhetorical effect, to stay in the character's way of thinking or speaking, to elicit a certain emotional response from readers, or to demonstrate your innate rebelliousness. These creative means are not intended to be used in the writing of standard academic essays and/or research papers which may be assigned in any course.

Talk with your instructor to determine the limitations, if any, on the correctness of your writing in the vernacular known as Standard Edited English. Thank you for your attention.

Have an amazingly awesome day! (Write something.)

---------------------------------------------------------------------

(C) Copyright 2010-2016 by Stephen M. Swartz. All Rights Reserved. No part of this blog, whether text or image, may be used without me giving you written permission, except for brief excerpts that are accompanied by a link to this entire blog.

Violators shall be written into novels as characters who are killed off. Serious violators shall be identified and dealt with according to the laws of the United States of America.

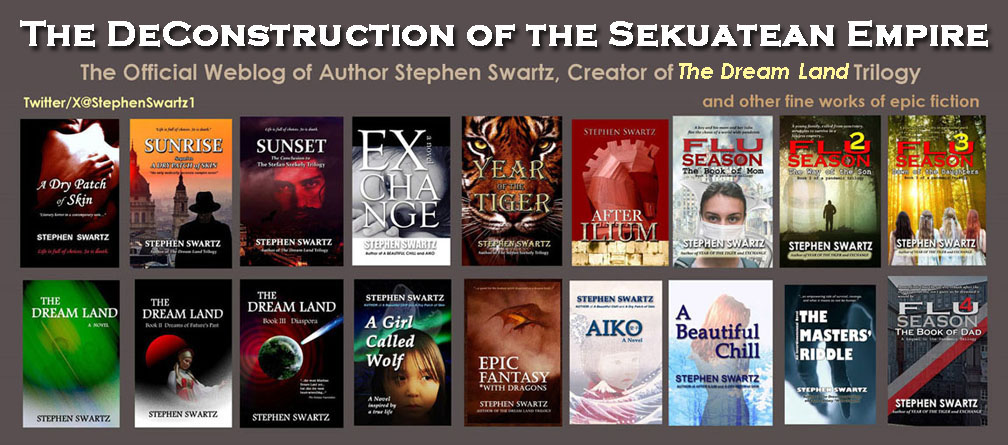

Even today, someone will ask me how I got the idea for my book - whatever my latest is - and I shrug humbly and say something like, "Well, I had a dream, see, and . . . ." The truth, however, may be much more ominous. In the case of my so-called "vampire" trilogy, there are two answers. The first book, A Dry Patch of Skin (referring to the first symptom of transforming into a vampire) was intended as a stand-alone novel, a one and done, because paranormal or Gothic or horror was not my usual genre. I just wanted to explain to my teenage daughter who was hooked on the Twilight series that vampirism was an actual disease affecting real people, something painful and disfiguring, not glittery and glamorous.

Even today, someone will ask me how I got the idea for my book - whatever my latest is - and I shrug humbly and say something like, "Well, I had a dream, see, and . . . ." The truth, however, may be much more ominous. In the case of my so-called "vampire" trilogy, there are two answers. The first book, A Dry Patch of Skin (referring to the first symptom of transforming into a vampire) was intended as a stand-alone novel, a one and done, because paranormal or Gothic or horror was not my usual genre. I just wanted to explain to my teenage daughter who was hooked on the Twilight series that vampirism was an actual disease affecting real people, something painful and disfiguring, not glittery and glamorous. Then I realized something from that vampire novel continued to pester me. What would happen next? That is always the bugbear for writers. We just cannot put it down, can't leave a sleeping bear alone, can't stop picking that scab. And so I conceived a new story, one that by necessity had to be less "medically accurate" and more along the lines of futuristic science fiction. Naturally I had to put myself in the shoes of my protagonist and hero, Stefan Szekely, who at the end of the first book, had accepted his sorry fate like a good trooper. How would he react to the passage of time? What would he want to do?

Then I realized something from that vampire novel continued to pester me. What would happen next? That is always the bugbear for writers. We just cannot put it down, can't leave a sleeping bear alone, can't stop picking that scab. And so I conceived a new story, one that by necessity had to be less "medically accurate" and more along the lines of futuristic science fiction. Naturally I had to put myself in the shoes of my protagonist and hero, Stefan Szekely, who at the end of the first book, had accepted his sorry fate like a good trooper. How would he react to the passage of time? What would he want to do? The Vampire Genre has developed its own tropes, symbols, motifs, and customs, starting with John Polidori's invention "The Vampyre" and fully realized in Bram Stoker's turn in Dracula. Others followed until the preponderance of the evidence created a vast multi-channel marketing juggernaut that an outsider could never hope to penetrate. And yet, it is the variety of vampire themes and story lines that give the genre so much richness. No one is solely correct about what a vampire is or is not. Not even me, though I profess to have written (Book 1, that is), a "medically accurate" version where our tragic hero transforms against his will into what he does not want to become. I continue to try to keep it as "real" as possible.

The Vampire Genre has developed its own tropes, symbols, motifs, and customs, starting with John Polidori's invention "The Vampyre" and fully realized in Bram Stoker's turn in Dracula. Others followed until the preponderance of the evidence created a vast multi-channel marketing juggernaut that an outsider could never hope to penetrate. And yet, it is the variety of vampire themes and story lines that give the genre so much richness. No one is solely correct about what a vampire is or is not. Not even me, though I profess to have written (Book 1, that is), a "medically accurate" version where our tragic hero transforms against his will into what he does not want to become. I continue to try to keep it as "real" as possible.