Last evening I went out to dinner with a friend and was asked the question I love to answer: Where do you get your book ideas? Yes, I could wax poetic for several minutes trying to answer that question. The short version is: I don't know.

I explained that it's rather like an infection. One germ grows into many, doubling then tripling in size, over and over until I am so full of that virus it explodes through me. I can no longer think or do anything else but write the damn story. Sometimes I try to write too soon and I get bogged down. Sometimes I wait too long to start writing and the story fades. By now, I know when to start and I try to choose the best time, set up the right environment, and close off the world to lay fingers to keyboard. Then magic happens. If I'm lucky, that is.

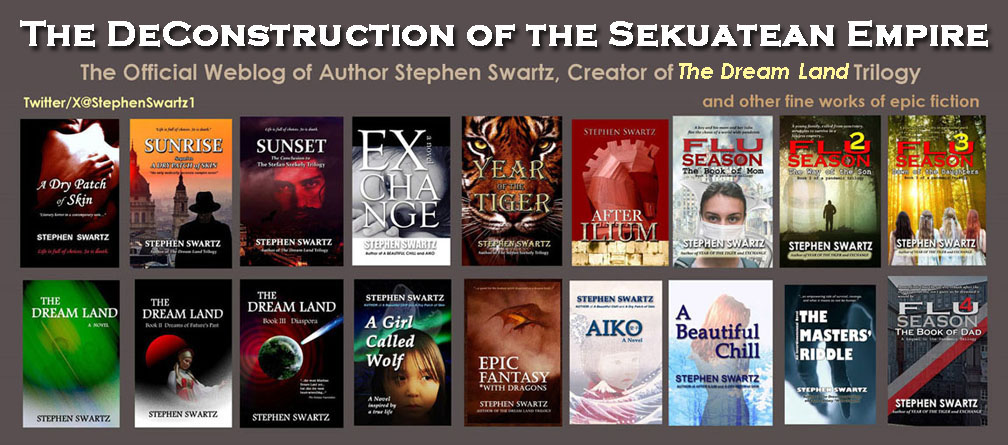

To understand how I came up with the idea for my newest novel AIKO, you can read my previous posts:

How I got the idea.

How I changed the idea.

Even now, I told my friend, I have a story boiling in me which started probably a year ago. Nothing specific happened that I can recall: just a few disparate images, words, maybe a meme on Facebook or a quirky tweet on Twitter--something jogs my brain and I let it stay. The germ will fade on its own or it will grow. The currently boiling idea occupies my waking moments. I have decided how it will begin and how it will proceed but not yet how it will end or what the actual arc of the story will be. See how it unfolds, partly following my commands and partly at random, is the fun part of writing.

Before I can write the new book, however, I must see the latest through to bookshelf status. I've dealt with the story of AIKO the previous two blog posts this month. Now it is time to do what is commonly called -da da da da da da daaaaaaah! the cover reveal. (In my linguistically-challenged psyche, I would argue that it should be a cover "revelation" not a "reveal"--but not worth a fight at this time.) I've teased readers on the previous two blog posts, so here is the -trumpets again- cover of my newest novel AIKO.

You might wonder about the elements of the cover. The famous woodblock print of Hokusai's The Great Wave of Kanagawa works well because the sea is a major plot point throughout the story although it is not a seafaring tale. The child image is important because the entire story revolves around what to do with this child. The Japanese characters (kanji) inside the O of AIKO serve to spell her name in the characters which are meaningful to the story--and explained in the book. SPOILER: One kanji character means 'love' and the other means 'child'.

So there you have it! AIKO is available in ebook for Kindle edition now and in print soon. It makes a great Father's Day story, as father and daughter meet and decide their future together.

---------------------------------------------------------------------

(C) Copyright 2010-2015 by Stephen M. Swartz. All Rights Reserved. No part of this blog, whether text or image, may be used without me giving you written permission, except for brief excerpts that are accompanied by a link to this entire blog.

Violators shall be written into novels as characters who are killed off. Serious violators shall be identified and dealt with according to the laws of the United States of America.

25 May 2015

17 May 2015

The Story of AIKO part 2

I took off from blogging for Mother's Day. Had motherly things to do. Besides, everyone would be blogging about the virtues of motherhood and I didn't feel I could contribute much, never having been a mother. Now, being a father...?

Well, I do have some experience. In fact, my cute little baby is graduating from high school tomorrow, already with a full life and career mapped out. I still remember the thrill I got when I told my father that I could celebrate Father's Day for the first time because I had a little one on the way. It was thrilling because for so many years of my youth he had sternly lectured me on staying straight and clean, focusing on school, and staying away from loose women who wanted nothing more than to trap me into a thankless marriage by allowing herself to get pregnant. His words. Bygones now....

Which brings me to Father's Day and the launching of my latest novel AIKO. It is about a man who finds he is a father. However, in order to celebrate Father's Day, he must overcome a lot of obstacles to claim his child. Perhaps it is a simple story. The details make it special. And yet, it is strangely similar to one of the grand opera stories of my youth: Madama Butterfly by Giacomo Puccini. (Here is the Metropolitan Opera's synopsis.)

As a music student in college, I was not averse to attending an opera or two. Some were more interesting musically than others. My mother, who always promoted my musical interests, took me to my first opera in Kansas City when I was a boy: Richard Wagner's The Flying Dutchman, about a ghost ship doomed to sail the seas forever. (Why is there no movie version today? It would make a great paranormal film.) But it was Madama Butterfly that became my favorite, and the only opera I can enjoy just listening to without having to see the whole stage production.

In the opera, an American naval officer visits Japan and because he is staying there a while on business, he arranges to have a "temporary" wife. The inevitable happens: his business is concluded and he leaves, promising to return, and later she discovers a child will be born. He does eventually return, but with his American wife in tow. He is surprised to find his Japanese lover has a child but he is determined to bring the child home to America. The Japanese woman is so distraught over that verdict that she commits suicide in one of opera's most tragic scenes.

While I was living in Japan in the late 1980s, teaching English to the middle school students of a small city, I wrote a story of an American man who meets a Japanese woman. They have a relationship then must inevitably part. A child is born. Eventually the man learns of the child's existence and wants to do the right thing. Despite his American wife's objection, he goes to Japan to check things out. I'm skipping over a lot of details, of course, but you can see how the basic plot is similar to the Madama Butterfly story. That was purely unintentional--unless a deeply rooted remembrance of the opera I had last seen a decade before somehow wormed its way through my brain and down to my fingertips clicking at the keyboard....

Seeing that similarity, I decided to exploit it and revised my story to use some elements of Madama Butterfly in a more overt fashion. First, I wanted to tell the story from the man's point of view. The opera is all from her side. Before I knew much about Japanese history and customs, I had always wondered why Cho-Cho-san (literally "Madame Butterfly") decided to kill herself to solve the problem. She should have killed him for trying to take away her child! Not to say any killing was acceptable, of course. Being in my Western mindset, I could not understand her motivations. Now I do. So in telling the story from his side, I would need to show him as a rational, responsible, do-the-right thing kind of guy who has all the best intentions in dealing with a tragedy.

The next thing I wanted to change was the time period. The opera is set at the turn-of-the-century when American naval forces first begin to rule the Pacific. In changing the setting to the late 1980s and early 1990s, I could exploit the new "internationalization" focus of Japan. Because of a booming economy and other nations' criticism of Japan's unfair trade practices, the government initiated (among other acts) the importing of foreign English teachers from the four English-speaking nations: USA, UK, Canada, and Australia. I was part of that influx of teachers who went to Japan through the Japan Exchange Teaching Program. So I was there at the exact time period of the story, and I described the clash of generations: the older World War II seniors and the pop culture youth who knew little about the war. It was an interesting yet awkward time. And it fit perfectly for my version of the story.

The next thing I wanted to change was the time period. The opera is set at the turn-of-the-century when American naval forces first begin to rule the Pacific. In changing the setting to the late 1980s and early 1990s, I could exploit the new "internationalization" focus of Japan. Because of a booming economy and other nations' criticism of Japan's unfair trade practices, the government initiated (among other acts) the importing of foreign English teachers from the four English-speaking nations: USA, UK, Canada, and Australia. I was part of that influx of teachers who went to Japan through the Japan Exchange Teaching Program. So I was there at the exact time period of the story, and I described the clash of generations: the older World War II seniors and the pop culture youth who knew little about the war. It was an interesting yet awkward time. And it fit perfectly for my version of the story.

So there you have it: Art imitating a life which imitates art.

Being a guy, of course I wanted the guy in my story to not be a jerk, to do the right thing. But he is human and thus has flaws. He also faces the clash of customs, lost among people who think differently, where the acts that make no sense to him seem perfectly logical to the local folk. Japan in the 1990s is a modern place, but in inaka (the rural, "backwoods" regions), the old, traditional ways still hold sway. So our hero, Benjamin Pinkerton (yes, I borrowed the name from the character in the opera, just to make the connection more obvious), tries to do the right thing: save a child he never knew he had while risking everything in his life back home. It is another stranger in a strange land scenario I like to write.

---------------------------------------------------------------------

(C) Copyright 2010-2015 by Stephen M. Swartz. All Rights Reserved. No part of this blog, whether text or image, may be used without me giving you written permission, except for brief excerpts that are accompanied by a link to this entire blog. Violators shall be written into novels as characters who are killed off. Serious violators shall be identified and dealt with according to the laws of the United States of America.

Well, I do have some experience. In fact, my cute little baby is graduating from high school tomorrow, already with a full life and career mapped out. I still remember the thrill I got when I told my father that I could celebrate Father's Day for the first time because I had a little one on the way. It was thrilling because for so many years of my youth he had sternly lectured me on staying straight and clean, focusing on school, and staying away from loose women who wanted nothing more than to trap me into a thankless marriage by allowing herself to get pregnant. His words. Bygones now....

Which brings me to Father's Day and the launching of my latest novel AIKO. It is about a man who finds he is a father. However, in order to celebrate Father's Day, he must overcome a lot of obstacles to claim his child. Perhaps it is a simple story. The details make it special. And yet, it is strangely similar to one of the grand opera stories of my youth: Madama Butterfly by Giacomo Puccini. (Here is the Metropolitan Opera's synopsis.)

As a music student in college, I was not averse to attending an opera or two. Some were more interesting musically than others. My mother, who always promoted my musical interests, took me to my first opera in Kansas City when I was a boy: Richard Wagner's The Flying Dutchman, about a ghost ship doomed to sail the seas forever. (Why is there no movie version today? It would make a great paranormal film.) But it was Madama Butterfly that became my favorite, and the only opera I can enjoy just listening to without having to see the whole stage production.

In the opera, an American naval officer visits Japan and because he is staying there a while on business, he arranges to have a "temporary" wife. The inevitable happens: his business is concluded and he leaves, promising to return, and later she discovers a child will be born. He does eventually return, but with his American wife in tow. He is surprised to find his Japanese lover has a child but he is determined to bring the child home to America. The Japanese woman is so distraught over that verdict that she commits suicide in one of opera's most tragic scenes.

While I was living in Japan in the late 1980s, teaching English to the middle school students of a small city, I wrote a story of an American man who meets a Japanese woman. They have a relationship then must inevitably part. A child is born. Eventually the man learns of the child's existence and wants to do the right thing. Despite his American wife's objection, he goes to Japan to check things out. I'm skipping over a lot of details, of course, but you can see how the basic plot is similar to the Madama Butterfly story. That was purely unintentional--unless a deeply rooted remembrance of the opera I had last seen a decade before somehow wormed its way through my brain and down to my fingertips clicking at the keyboard....

Seeing that similarity, I decided to exploit it and revised my story to use some elements of Madama Butterfly in a more overt fashion. First, I wanted to tell the story from the man's point of view. The opera is all from her side. Before I knew much about Japanese history and customs, I had always wondered why Cho-Cho-san (literally "Madame Butterfly") decided to kill herself to solve the problem. She should have killed him for trying to take away her child! Not to say any killing was acceptable, of course. Being in my Western mindset, I could not understand her motivations. Now I do. So in telling the story from his side, I would need to show him as a rational, responsible, do-the-right thing kind of guy who has all the best intentions in dealing with a tragedy.

The next thing I wanted to change was the time period. The opera is set at the turn-of-the-century when American naval forces first begin to rule the Pacific. In changing the setting to the late 1980s and early 1990s, I could exploit the new "internationalization" focus of Japan. Because of a booming economy and other nations' criticism of Japan's unfair trade practices, the government initiated (among other acts) the importing of foreign English teachers from the four English-speaking nations: USA, UK, Canada, and Australia. I was part of that influx of teachers who went to Japan through the Japan Exchange Teaching Program. So I was there at the exact time period of the story, and I described the clash of generations: the older World War II seniors and the pop culture youth who knew little about the war. It was an interesting yet awkward time. And it fit perfectly for my version of the story.

The next thing I wanted to change was the time period. The opera is set at the turn-of-the-century when American naval forces first begin to rule the Pacific. In changing the setting to the late 1980s and early 1990s, I could exploit the new "internationalization" focus of Japan. Because of a booming economy and other nations' criticism of Japan's unfair trade practices, the government initiated (among other acts) the importing of foreign English teachers from the four English-speaking nations: USA, UK, Canada, and Australia. I was part of that influx of teachers who went to Japan through the Japan Exchange Teaching Program. So I was there at the exact time period of the story, and I described the clash of generations: the older World War II seniors and the pop culture youth who knew little about the war. It was an interesting yet awkward time. And it fit perfectly for my version of the story.So there you have it: Art imitating a life which imitates art.

Being a guy, of course I wanted the guy in my story to not be a jerk, to do the right thing. But he is human and thus has flaws. He also faces the clash of customs, lost among people who think differently, where the acts that make no sense to him seem perfectly logical to the local folk. Japan in the 1990s is a modern place, but in inaka (the rural, "backwoods" regions), the old, traditional ways still hold sway. So our hero, Benjamin Pinkerton (yes, I borrowed the name from the character in the opera, just to make the connection more obvious), tries to do the right thing: save a child he never knew he had while risking everything in his life back home. It is another stranger in a strange land scenario I like to write.

---------------------------------------------------------------------

(C) Copyright 2010-2015 by Stephen M. Swartz. All Rights Reserved. No part of this blog, whether text or image, may be used without me giving you written permission, except for brief excerpts that are accompanied by a link to this entire blog. Violators shall be written into novels as characters who are killed off. Serious violators shall be identified and dealt with according to the laws of the United States of America.

02 May 2015

The Story of AIKO

Last month in this blog, I revisited Korea and got a good dose of nostalgic thrill. Further back in this blog I wrote about another trip to Korea. It's ironic, however, that much more of my time in Asia was spent in Japan. Five years total, in fact, which is a tenth of my life--or a sixth of my adult years!

As a foreign teacher, my everyday mundane activities were not very exciting--unless you happened to be family members who were curious about everything I was doing there or you were interested in semi-rural and small town Japan life in the late 1980s and early 1990s. As it was, Japan was beginning its "internationalization" program, which included bringing thousands of English-speaking young people from the U.S., U.K., Canada, and Australia to Japan to help teach English in the public schools.

As a foreign teacher, my everyday mundane activities were not very exciting--unless you happened to be family members who were curious about everything I was doing there or you were interested in semi-rural and small town Japan life in the late 1980s and early 1990s. As it was, Japan was beginning its "internationalization" program, which included bringing thousands of English-speaking young people from the U.S., U.K., Canada, and Australia to Japan to help teach English in the public schools.

I was one of them. It was an experience that was equal parts fascinating and frustrating. The fascination came from discovery of a completely new and different culture from what I had known in my own country, not the tourist sort but right down to the everyday getting through life kind of things. The frustrating part was trying to adapt to a set of customs that did not come naturally to me as well as trying to see things from a different perspective and understanding how in the world it could possibly work just fine that way.

I went first to Saga City, capital of Saga prefecture (state), on the southwest major island of Kyushu, and lived there for two years. I rotated with another American teacher among the city's nine middle schools--when the kids first start to learn English. The city was surrounded by rice fields as far as you could see. It had the remains of a castle. I rode a bicycle everywhere, sometimes the local bus. I ate mostly the Japanese food available to me although there were also plenty of fast food restaurants in town.

Enjoying the English teacher life, I decided it might be a good career move fpr me to become an official English teacher in the U.S., so I returned and entered an Education program back home. I completed everything but the student-teaching semester when I got an offer to return to Japan that I could not pass up.

Enjoying the English teacher life, I decided it might be a good career move fpr me to become an official English teacher in the U.S., so I returned and entered an Education program back home. I completed everything but the student-teaching semester when I got an offer to return to Japan that I could not pass up.

With more credentials, I arrived in Okayama prefecture, mid-way between Hiroshima and Kobe on the main island of Honshu. I served as the one and only English teacher for three middle schools up in the mountains, living in the village where my main school was and commuting once each week to the other two. It was a picturesque landscape and I settled in rather comfortably. It felt odd when visiting relatives in America for Christmas holiday to "go home" to Japan; my apartment in Nariwa, Okayama felt more like my home than the Kansas City where I'd grown up.

I'm not sure where all this love for Japanese culture began. I can pick out a few starting points, but the main idea of telling all of this is to contrast my actual life in Japan with all the reports about Korea I've posted. They are two very different places--yet to the casual Western tourist somewhat similar. In blogging, I've tried to offer mostly the humorous side of my travels: the stranger in a strange land scenario, where I struggle to understand, often insisting my way is the best way, even the only way, then being soundly corrected. In such a way the stranger comes to appreciate, even prefer, the new culture.

I'm not sure where all this love for Japanese culture began. I can pick out a few starting points, but the main idea of telling all of this is to contrast my actual life in Japan with all the reports about Korea I've posted. They are two very different places--yet to the casual Western tourist somewhat similar. In blogging, I've tried to offer mostly the humorous side of my travels: the stranger in a strange land scenario, where I struggle to understand, often insisting my way is the best way, even the only way, then being soundly corrected. In such a way the stranger comes to appreciate, even prefer, the new culture.

It's kind of like James Clavell's Shogun, where the shipwrecked Englishman gradually becomes Japanese and takes his place in that feudal society. A similar transformation is depicted in the Tom Cruise film The Last Samurai. Those may have been full of cliches and stereotypes, of course (although I trust Clavell to get the facts straight). For some of us, there is something attractive about that culture. I gradually slipped into that culture, too, and I became a stranger when returning to the country of my birth. (Plenty of other examples of this kind of scenario exist that involve other cultures than Japanese.)

It's kind of like James Clavell's Shogun, where the shipwrecked Englishman gradually becomes Japanese and takes his place in that feudal society. A similar transformation is depicted in the Tom Cruise film The Last Samurai. Those may have been full of cliches and stereotypes, of course (although I trust Clavell to get the facts straight). For some of us, there is something attractive about that culture. I gradually slipped into that culture, too, and I became a stranger when returning to the country of my birth. (Plenty of other examples of this kind of scenario exist that involve other cultures than Japanese.)

This "stranger in a strange land" theme seems to have become my writing focus, my stock in trade. All of my novels deal with characters being in a new and different place than they grew up in. I even took it so far as to have them visit another planet in THE DREAM LAND Trilogy; the Earthling travelers were both amazed and frustrated by what they found. That "stranger" theme usually involves someone also speaking a foreign language and speaking English imperfectly. I'm an English teacher by trade, after all, and a linguist by training, so the language aspects of characters have always fascinated me. (You can see a chart here of what places and languages are in each of my novels.)

So it should come as no surprise that my forthcoming novel AIKO follows that same theme: the stranger coming to the strange land and having to make his way and reach his goal, thwarted at every turn by the rules and customs he does not know, does not understand, or refuses to adapt to. The novel is also set in Japan, a place I feel thoroughly confident in describing--at least from the Western stranger's perspective. I lived in two places there and visited many other locations--all of the big tourist spots as well as places tourists do not visit. I also visited the locations in the novel.

The story of AIKO is a quest to make things right, to restore a balance in the protagonist's and everyone else's lives. As with any good story, it begins with a conflict, a problem needing to be solved. Our hero tries to solve the problem but finds obstacles. He tries to overcome the obstacles but things get worse. He starts to believe he won't succeed yet fights harder, refusing to give up. Will he succeed or not is the story, of course. In that sense, it's quite simple. The beauty is in the details.

The story of AIKO is a quest to make things right, to restore a balance in the protagonist's and everyone else's lives. As with any good story, it begins with a conflict, a problem needing to be solved. Our hero tries to solve the problem but finds obstacles. He tries to overcome the obstacles but things get worse. He starts to believe he won't succeed yet fights harder, refusing to give up. Will he succeed or not is the story, of course. In that sense, it's quite simple. The beauty is in the details.

I've chosen to set this plot in the Japan on the cusp of its internationalization program, a time in the early 1990s when old thinking clashed with modern thinking. The fate of a child is left to the effort of this stranger struggling through this strange land, who is trying to do the right thing--even at the risk of destroying his marriage and losing his career. The situation gets quite desperate for him as he is soon fighting the calendar as well as the bureaucracy Japan is famous for. And then there is the waitress who wants him to take her back to America and the gangster wannabes who just like having fun with this foreign guy.

It was only after writing the initial draft that I recognized some similarities between my story and the story at the heart of the opera Madame Butterfly--similarities which I sought to emphasize, even exploit, in subsequent drafts. I'll tell you about that next time.

---------------------------------------------------------------------

(C) Copyright 2010-2015 by Stephen M. Swartz. All Rights Reserved. No part of this blog, whether text or image, may be used without me giving you written permission, except for brief excerpts that are accompanied by a link to this entire blog. Violators shall be written into novels as characters who are killed off. Serious violators shall be identified and dealt with according to the laws of the United States of America.

As a foreign teacher, my everyday mundane activities were not very exciting--unless you happened to be family members who were curious about everything I was doing there or you were interested in semi-rural and small town Japan life in the late 1980s and early 1990s. As it was, Japan was beginning its "internationalization" program, which included bringing thousands of English-speaking young people from the U.S., U.K., Canada, and Australia to Japan to help teach English in the public schools.

As a foreign teacher, my everyday mundane activities were not very exciting--unless you happened to be family members who were curious about everything I was doing there or you were interested in semi-rural and small town Japan life in the late 1980s and early 1990s. As it was, Japan was beginning its "internationalization" program, which included bringing thousands of English-speaking young people from the U.S., U.K., Canada, and Australia to Japan to help teach English in the public schools. I was one of them. It was an experience that was equal parts fascinating and frustrating. The fascination came from discovery of a completely new and different culture from what I had known in my own country, not the tourist sort but right down to the everyday getting through life kind of things. The frustrating part was trying to adapt to a set of customs that did not come naturally to me as well as trying to see things from a different perspective and understanding how in the world it could possibly work just fine that way.

I went first to Saga City, capital of Saga prefecture (state), on the southwest major island of Kyushu, and lived there for two years. I rotated with another American teacher among the city's nine middle schools--when the kids first start to learn English. The city was surrounded by rice fields as far as you could see. It had the remains of a castle. I rode a bicycle everywhere, sometimes the local bus. I ate mostly the Japanese food available to me although there were also plenty of fast food restaurants in town.

Enjoying the English teacher life, I decided it might be a good career move fpr me to become an official English teacher in the U.S., so I returned and entered an Education program back home. I completed everything but the student-teaching semester when I got an offer to return to Japan that I could not pass up.

Enjoying the English teacher life, I decided it might be a good career move fpr me to become an official English teacher in the U.S., so I returned and entered an Education program back home. I completed everything but the student-teaching semester when I got an offer to return to Japan that I could not pass up.With more credentials, I arrived in Okayama prefecture, mid-way between Hiroshima and Kobe on the main island of Honshu. I served as the one and only English teacher for three middle schools up in the mountains, living in the village where my main school was and commuting once each week to the other two. It was a picturesque landscape and I settled in rather comfortably. It felt odd when visiting relatives in America for Christmas holiday to "go home" to Japan; my apartment in Nariwa, Okayama felt more like my home than the Kansas City where I'd grown up.

I'm not sure where all this love for Japanese culture began. I can pick out a few starting points, but the main idea of telling all of this is to contrast my actual life in Japan with all the reports about Korea I've posted. They are two very different places--yet to the casual Western tourist somewhat similar. In blogging, I've tried to offer mostly the humorous side of my travels: the stranger in a strange land scenario, where I struggle to understand, often insisting my way is the best way, even the only way, then being soundly corrected. In such a way the stranger comes to appreciate, even prefer, the new culture.

I'm not sure where all this love for Japanese culture began. I can pick out a few starting points, but the main idea of telling all of this is to contrast my actual life in Japan with all the reports about Korea I've posted. They are two very different places--yet to the casual Western tourist somewhat similar. In blogging, I've tried to offer mostly the humorous side of my travels: the stranger in a strange land scenario, where I struggle to understand, often insisting my way is the best way, even the only way, then being soundly corrected. In such a way the stranger comes to appreciate, even prefer, the new culture. It's kind of like James Clavell's Shogun, where the shipwrecked Englishman gradually becomes Japanese and takes his place in that feudal society. A similar transformation is depicted in the Tom Cruise film The Last Samurai. Those may have been full of cliches and stereotypes, of course (although I trust Clavell to get the facts straight). For some of us, there is something attractive about that culture. I gradually slipped into that culture, too, and I became a stranger when returning to the country of my birth. (Plenty of other examples of this kind of scenario exist that involve other cultures than Japanese.)

It's kind of like James Clavell's Shogun, where the shipwrecked Englishman gradually becomes Japanese and takes his place in that feudal society. A similar transformation is depicted in the Tom Cruise film The Last Samurai. Those may have been full of cliches and stereotypes, of course (although I trust Clavell to get the facts straight). For some of us, there is something attractive about that culture. I gradually slipped into that culture, too, and I became a stranger when returning to the country of my birth. (Plenty of other examples of this kind of scenario exist that involve other cultures than Japanese.)This "stranger in a strange land" theme seems to have become my writing focus, my stock in trade. All of my novels deal with characters being in a new and different place than they grew up in. I even took it so far as to have them visit another planet in THE DREAM LAND Trilogy; the Earthling travelers were both amazed and frustrated by what they found. That "stranger" theme usually involves someone also speaking a foreign language and speaking English imperfectly. I'm an English teacher by trade, after all, and a linguist by training, so the language aspects of characters have always fascinated me. (You can see a chart here of what places and languages are in each of my novels.)

So it should come as no surprise that my forthcoming novel AIKO follows that same theme: the stranger coming to the strange land and having to make his way and reach his goal, thwarted at every turn by the rules and customs he does not know, does not understand, or refuses to adapt to. The novel is also set in Japan, a place I feel thoroughly confident in describing--at least from the Western stranger's perspective. I lived in two places there and visited many other locations--all of the big tourist spots as well as places tourists do not visit. I also visited the locations in the novel.

The story of AIKO is a quest to make things right, to restore a balance in the protagonist's and everyone else's lives. As with any good story, it begins with a conflict, a problem needing to be solved. Our hero tries to solve the problem but finds obstacles. He tries to overcome the obstacles but things get worse. He starts to believe he won't succeed yet fights harder, refusing to give up. Will he succeed or not is the story, of course. In that sense, it's quite simple. The beauty is in the details.

The story of AIKO is a quest to make things right, to restore a balance in the protagonist's and everyone else's lives. As with any good story, it begins with a conflict, a problem needing to be solved. Our hero tries to solve the problem but finds obstacles. He tries to overcome the obstacles but things get worse. He starts to believe he won't succeed yet fights harder, refusing to give up. Will he succeed or not is the story, of course. In that sense, it's quite simple. The beauty is in the details. I've chosen to set this plot in the Japan on the cusp of its internationalization program, a time in the early 1990s when old thinking clashed with modern thinking. The fate of a child is left to the effort of this stranger struggling through this strange land, who is trying to do the right thing--even at the risk of destroying his marriage and losing his career. The situation gets quite desperate for him as he is soon fighting the calendar as well as the bureaucracy Japan is famous for. And then there is the waitress who wants him to take her back to America and the gangster wannabes who just like having fun with this foreign guy.

It was only after writing the initial draft that I recognized some similarities between my story and the story at the heart of the opera Madame Butterfly--similarities which I sought to emphasize, even exploit, in subsequent drafts. I'll tell you about that next time.

---------------------------------------------------------------------

(C) Copyright 2010-2015 by Stephen M. Swartz. All Rights Reserved. No part of this blog, whether text or image, may be used without me giving you written permission, except for brief excerpts that are accompanied by a link to this entire blog. Violators shall be written into novels as characters who are killed off. Serious violators shall be identified and dealt with according to the laws of the United States of America.

Labels:

adoption,

aiko,

english teacher,

honshu,

interracial,

james clavell,

japan,

korea,

kyushu,

madame butterfly,

novel,

okayama,

romance,

saga,

shogun,

stranger,

the dream land,

the last samurai,

tom cruise

18 April 2015

Land of the Morning Calm part 3

As all good travelogues must, I struggle to walk a fine line between telling a rousing story of adventure and sharing the exact yet possibly less-interesting truth of exactly what happened. For drama's sake, I share here the best and worst part of my trip. It is perhaps ironic that even as I prepare this posting today, I am again fighting a monster illness of similar voracity as I did during that spring break week in 1992.

You can read Part 2 here and, if you happen to be further out of date, Part 1 here.

As you may recall from Part 2, I was trying to make the best of my sightseeing situation despite a monster cold complete with sore throat and nasal drainage, headache and body aches. What got me through it was a magic elixir provided by the Korean pharmacist. After visiting the tourist sites of Ch’ônmach’ong, Pulguk-sa, Sokkuram, and Anap'chi, I got on a bus heading across the Korean peninsula to Kyong-ju....

The scenery I saw outside the bus windows was quite plain at first, brown hills and brown farms, but I kept looking for some mountains that looked like the ones at the beginning of the M*A*S*H programs every week—you know, the pair of bare, rocky peaks the helicopters descend from. The land was pretty dry, also it was between winter and spring, a time when nothing is growing and everything looks brown. But later, after we passed Taegu—and didn’t stop; it really was an express bus—we switched over to the ’88 Olympic Expressway, a brand-new highway cutting through the mountainous Chirisan National Park.

There

were several bare rock mountains, looking similar to the M*A*S*H programs. The farm villages we passed were

primitive-looking, however. Maybe I

wasn’t so surprised after my experiences in Pusan and Ulsan, but still, seeing

the little shacks, or nicer adobe houses with their little walls

surrounding the front yard, again made me wonder if Korea was really such a

modern country. The sight of farmers

behind a plow pulled by an ox was something I was not expecting. I wanted to get a picture of a “cow-plow” but

it was difficult to spot a brown cow against the brown dirt, but finally I got

one.

Finally we did stop for a restroom break, at

the Chirisan Service Area. Over the entrance was a sign duplicating the five Olympic rings. In all, it was an uneventful trip, as I

listened to cassettes I'd bought in Ulsan using my Walkman, and watched the scenery,

waiting with camera in hand for any dramatic scenery to photograph. The pictures came out a little dark because I

had to set the shutter speed fast to stop the picture—as fast as the bus was

going.

About

4 hours after leaving Kyong-ju, we arrived in Kwang-ju—which was about 2

pm. I got off the bus and went into the

terminal to look for my second friend, my pen-pal Joung-Jin [“JJ,” her

English nickname]. I had called her the night before to say when I was arriving, and she said she would

meet me at the bus terminal, which meant that she would be driving from her

home in Mokp’o up to Kwang-ju, an hour and a half drive. Inside the terminal, however, there was nobody I

recognized and no room to sit down, so I went outside and stood by the front door, near the

taxi stand—where every driver there wanted me to take his cab. I parked myself where I

could keep an eye on both directions at once.

It was warm and sunny and Kwang-ju appeared to be a decent city. After about 15 minutes, I saw JJ

walking along the sidewalk toward me.

She said that her friend, English name “Sue,” was supposed to meet us

here, so we waited another 10 minutes until Sue arrived. Then

we walked to where JJ’s car was parked—near the “local” bus terminal, where

they had expected me to arrive.

JJ’s friend “Sue” was a middle school biology teacher but she took the afternoon off to

brush up on her English, and the two of them bundled me into their car, a red sports car, and we drove off down the same highway I had just been riding the bus on. We drove along for about 45

minutes before exiting and burning down a road that wound up through the hills

to Songwang-sa, another temple deep in the woods. JJ liked to drive, it seemed, but after 4 hours on a bus, I would have benefited from a slower, less ferocious driving style, especially riding in the cramped back seat.

JJ’s friend “Sue” was a middle school biology teacher but she took the afternoon off to

brush up on her English, and the two of them bundled me into their car, a red sports car, and we drove off down the same highway I had just been riding the bus on. We drove along for about 45

minutes before exiting and burning down a road that wound up through the hills

to Songwang-sa, another temple deep in the woods. JJ liked to drive, it seemed, but after 4 hours on a bus, I would have benefited from a slower, less ferocious driving style, especially riding in the cramped back seat.

The temple of Songwang-sa ("sa" means temple) was nearly empty at that afternoon hour and the souvenir shops looked closed. My escorts decided I must be hungry from my long

trip, missing lunch while riding on the bus, so our first stop was the cafe

there among the souvenir stands. Again

we had the traditional many dishes dinner, which JJ

said did not include very many good things.

At least it was cheap. JJ insisted on paying for everything—for my entire stay, in fact, even to

the point where I was begging for the chance to pay for something.

We walked through the temple, a

very nice and colorful place. Certainly, I would not have been able to visit such a place if I was traveling by myself. In the temple’s gatehouse were the giant

wooden statues of the guardians, one I recognized from a postcard I had sent

out the day before.

The face was about 6 feet across and a

paler shade of pink than on the postcard picture. Inside the courtyard, several worshipers

were waving incense around and bowing down on their knees. As we walked around and I took

pictures, a couple tour groups arrived and filled the courtyard. We didn't stay long. JJ said that she was

never really interested in temples but understood that Westerners like to see

them.

So

we drove back, but they decided they didn’t want to pay the expressway toll

again, so we wound around a large lake and along back country roads. It was scenic around the lake, and I was able

to see the “real” countryside of dirty villages, but having spent 4 hours on

the bus, and another 45 minutes in the car, and now not knowing how much longer

the ride would be, I was getting car sick.

Probably the fact that my cold was so bad was the reason that I was

distracted at all from my stomach.

Actually, the cough syrup was wearing off and

my head and sinuses were beginning to feel pressure pain. But soon we made it back into Kwang-ju,

and they drove me around the city, seeing some of the sights. It was nearing dusk by then and so they took me up to Moon Mountain.

I

took some pictures of Kwang-ju from the outlook on the mountain, which looked

nice the way the sun was setting on the western horizon. We passed the university, which had interesting architecture, the

buildings all white and with high-peaked roofs, like Swiss chalets, nothing like

Korean style. We stopped for dinner at a "French" restaurant after dark and had a pizza. Sue said goodnight then and JJ drove us down

to Mokp’o, the seaport on the end of the peninsula.

In

the darkness, of course I couldn't see much.

But when we entered the town, she pointed out a few landmarks and then

suddenly we pulled up in front of a white-walled building. Out came JJ’s mother and little brother to greet me

through the iron gate. Once inside

their house, I was shown to the guest room and offered more to eat and

drink. But I was dead tired and my cold

was worse so they said they would take me to see their doctor in the

morning. He was a relative, JJ said, so it would be easy for me to get in.

Well,

they say Korea is the “Land of the Morning Calm” but I never found any morning

to suggest the origin of that nickname.

JJ’s mother is a music teacher, I quickly learned, and JJ is a private

English teacher, so their students come before and after the regular public

school hours. Thus, at 6 a.m., the opposite side

of the wall near the head of my bed was filled with the strains of six pianos loudly playing scales up and down the keyboard.

And it didn't stop until 7:45 when the kids left for school!

That first morning, I decided I might as well get up and get into the

bathroom and take a shower while the room was free. Then, dressed for the day, I lay back down once the

music stopped. Until I was called for breakfast.

Well, the Korean traditional breakfast is just about whatever they would

have at lunch or dinner. JJ preferred a

Western style breakfast, but this morning settled for Korean style on my account. Then we all got into the car and went off to

the doctor. Her little brother, a 6th grader, we dropped off at school first.

The

doctor’s office was packed and noisy when we stepped inside. I sure got my share of stares by the locals, but

we did get right in and the doctor spoke to me in English—even as old ladies sitting

around his office kept cutting in shouting their questions and complaints and

he shouted back at them to wait their turn or whatever. He diagnosed that I had a I cold and

prescribed medicine, 7 pills (one for each symptom) to be taken 3 times a day

(a 4 day supply). JJ insisted on paying for my medicine at the pharmacy there inside the clinic. No more delicious super-codeine cough syrup!

Then we swung by the

post office to double check the postage on my postcards and buy a few extra

stamps for other postcards—and I mailed the ones I had finished. We had met JJ’s grandmother there at the clinic

and JJ said she didn’t speak any English, but after we all returned to the

house, we got into a conversation, and she was fluent!—in Japanese. I couldn’t keep up, and I heard all of the

little particles sprinkled among the words I understood and I knew that she was

good, so I tried to say what I could to be polite. The gist of what she said was that either her

brother or her former, now deceased husband was a student at Waseda University in

Tokyo and that he wrote his letters to her in Japanese, so she learned to read

it.

JJ and I went for a drive through the city of Mokp'o and out to the shore. We went to a park to climb a mountain, Yudalsan, which

overlooks both the city and the harbor, and on the opposite side, the ocean

itself. I was interested in the mountain

from the first moment I saw it, because it had lots of “bare rock” for dramatic effect. I explained that since I was from Kansas, a

land where you could drive for six hours and not even see hills, mountains in

general and especially those with dramatic scenery, mostly in the form of bare

rock faces and peaks, interested me the most.

At the base of the mountain, by the parking

lot, was a statue of Admiral Yi, who a few hundred years ago invented the first

armored fighting ships, which were called “turtle boats.” Legend also had it that he had the mountain

completely covered with straw so that the invading Japanese forces would see it

and think it was a huge pile of rice for the Korean army and overestimate its

size. I’m not sure if it worked or not,

but Hideyoshi did invade Korea eventually—at least he tried. The Japanese navy was turned back by the turtle boats. Unfortunately, it

was a hazy morning, and me being the only foreigner in all of Mokp’o (probably), I got many stares as we climbed the mountain.

From the top of the larger peak, we had a good view of the city.

After climbing

down, we drove around the mountain and out the road along the seaside. The sun began

shining through the clouds. Back in town, we

stopped to pick up some hamburgers at “Big Boy” and took them out to the dam to

eat. An inlet of the sea had been dammed to create a fresh-water reservoir. The hamburgers

weren't too bad, but the French fries were awful. We walked to a building nearby which turned

out to be a restaurant and souvenir shop and got some ice cream.

Heading

back to Mokp’o, we stopped at the “Cultural Hall of the Country.” JJ said she had never been inside but was

told it was a kind of rock garden. So in

we went. Behind the building was indeed

a yard with many strangely shaped rocks and stones there, some with colorful

flowers around them. But inside the

building, it was like a rock museum, with two large rooms of stones on display. There were naturally formed stones in shapes which resembles something else, like a rabbit

or a crane. There were stones which looked like rough-cut miniature islands, many set in pans of water to better simulate the effect. And there were stones which had

some intrusions of minerals which served to give them a “picture” of something

on their face. Each

rock had a sign with the name given to the piece and

where it was found. Some of the names

did not fit what we thought it looked like.

We started laughing at how silly it seemed to be looking at all of these

rocks, but as we went on it became fun, because we started to give our own

names to the rocks.

It

was getting late, so we headed back to JJ’s house. I took a short nap before her 5:00 class of

6th graders. I was to be a guest in the

class, and all of the students (including her brother) had to introduce

themselves to me and ask me questions.

Later I helped to teach them the numbers 1-10 by assigning a number to

each student and calling a number at random; the others had to point to that student whose number I called. Of course, the faster I called numbers the more fun it

was. But then I was

excused—I was beginning to lose my voice anyway. It was time for JJ to teach the grammar

part of the lesson. After that class, we

had supper—the same many dishes of Korean goodies. That

was it for me that evening, and I took my medicine and went to bed early.

The

next day (Wednesday, I think it was), I woke at 6 am to the sound of music

again, but I got up and got dressed to go with JJ to her kendo

practice. It was in a small dôjo behind the city stadium about a

kilometer from their house. The kendo

master, a man of about 60 and very tall for a Korean, was surprised to see me

enter the dôjo but he was friendly

and shook my hand. I watched the

practice. JJ was in full armor and had good form,

having been studying every morning for six months. Her brother also practiced but

he was prone to showing off.

Then we returned to the house for breakfast. This lifestyle in Mokp’o was beginning to

remind me of my army training, where we got up early and had a full-day’s

schedule before breakfast, and then had a really

full day after.

Then

about 9 o’clock, another friend of JJ’s arrived to take us to another

temple. JJ didn’t know the way and

didn’t want to drive so far, so she invited her friend—I never caught his name

except his family name was pronounced “Moon”—who had a bigger, more comfortable

car. So the three of us drove out of

Mokp’o, back across the dam, and into the hills to the east, and an hour later

arrived at Turyunsan State Park.

The

temple wasn't so big but the main thing there was the mountain scenery and the

hiking trails. My guide book continually

stressed that Korean people loved mountain climbing but JJ continually insisted

that she was one who did not like mountain climbing. So we went only a little way. With my cold moving up into my head and my eyes itchy and my nose runny, I did not feel much like a long

expedition, but being out in the sunny, fresh air seemed to make me feel

better. There was a nice waterfall where

we took turns taking pictures.

The scenery was lovely springtime scenery, the cherry tree blossoms

and yellow flowers and greenery of the mountains

with the bare rock, and the stream gurgling down among the boulders—it was peaceful.

Next we went to the memorial park of Wang-In.

Who was Wang-In? Little did I

know but soon learned, he was the Korean who went to Japan to teach the Chinese

characters to the royal court. In other

words, he taught the Japanese all of those strange characters

called kanji. Should he be thanked or cursed for that? Well, in Korea they praised

him with this memorial. He also taught

the royal court the principles of Buddhism.

The main memorial was a three-tiered display with separate shrines and

monuments. Out from the memorial proper

was his restored birthplace and up on the mountainside another temple for praying

to his spirit. In the main memorial, one

large building housed Western-style oil paintings from the life of

Wang-In. The picture of Wang-In as a baby

looks like the manger scene in Christian texts.

On

the way back to Mokp'o, we stopped for a late lunch in some dusty town. I learned later that they were Mr. Moon’s relatives. The dinner was a dish similar to Bulgogi. The appetizers were

certainly interesting: assorted raw fish and seafood. I tried a few that looked safe. Then came the bowl of octopus—freshly cut, white-gray, wiggling—and I didn't think that I could

indulge in that local specialty. I

was encouraged to try it, however, so I lowered my chopsticks but as I tried to grab a

piece of severed tentacle, the piece of tentacle wiggled and grabbed onto the bowl and I couldn't pull it off with my chopsticks. That’s enough, I

said. Mr. Moon tried one and announced

that he felt it wiggling as it went down his throat.

Back

at JJ’s house, we went through our usual evening classes, and we had a dinner of Kalpi—the barbecues ribs that are famous—prepared by the mother of one of the students. Many of the students came for music lessons

and stayed for English lessons. Every

hour was a different grade of students: 6th graders, middle school, high

school, and one college girl. JJ said

she canceled her private adult lessons this week for my visit, but

the younger students she wanted to meet me, a real native speaker.

Back

at JJ’s house, we went through our usual evening classes, and we had a dinner of Kalpi—the barbecues ribs that are famous—prepared by the mother of one of the students. Many of the students came for music lessons

and stayed for English lessons. Every

hour was a different grade of students: 6th graders, middle school, high

school, and one college girl. JJ said

she canceled her private adult lessons this week for my visit, but

the younger students she wanted to meet me, a real native speaker.

Later I asked her what she charged her

students and she told me 150,000 Won per week. So, at four lessons a week,

counting just the fifteen or so students I met, times the 150,000

Won, times four weeks per month--that is a handsome income indeed! No wonder she could afford to pay for everything during my stay,

including my cold medicine and any souvenir I picked out to buy for myself. Whenever I tried to give a gift for her

and her family’s hospitality, they gave me a return present. Consequently, I returned with about as much

as I brought with me from Japan.

After

dinner, we went out to find a bookshop where I could buy a map of Mokp’o, and a

music shop where I could browse. JJ took me into a crowded music shop stacked

from floor to ceiling with cassettes and CDs but it seemed too daunting for me

to browse through every spine label with all the other customers staring at me. I really was the only Westerner in Mokp'o, it seemed. But everyone

seemed to know JJ and she got her way wherever we went. The bookshop, however, was a disappointment. We went to the biggest one in town but they

only had books—no magazines, no newspapers, nothing but books, only books, and

nothing in English except textbooks. So

we stopped at a travel agency and I got a simplified map of the state and a

tourist guidebook in English.

Back

home, I began the task of packing everything, shuffling my dirty clothes around

and saving my fresh clothes. We had checked the schedules of buses and

trains and concluded that the most efficient way for me to get back to Pusan for my

flight to Fukuoka was to take a six-hour bus directly from Mokp’o to Pusan,

leaving at 10 am and arriving at 4 pm. With enough drinks and snacks for the trip, I climbed aboard and waved goodbye to JJ.

The bus took the back roads at first, going through various seaside towns east of

Mokp’o. The trip was uneventful, except

for a group of high school students who were joking around in the back seats

and caused the bus driver to stop and scold them a few times. They also kept asking him to let them take a

restroom break at several stops along the way other than the designated

restroom break stop. The bus seemed to stop at every little town’s bus terminal

to pick up or let off a passenger. Once

we connected with the Nanhae Expressway, it was non-stop to Pusan.

Once

in the environs of Pusan, I was worried which terminal the bus would go

to: the dirty “local” bus terminal Eun-Sook and I had arrived at from the airport, or

the “express” bus terminal next to the McDonald’s. The main difference was whether I would have to take a taxi to complete my journey. If the express terminal, I could

walk a couple blocks to the subway and take it down into the city and walk a

couple more blocks to my hotel for the night.

But, it was not to be. It went to

the same dirty terminal as before.

As

soon as I got out of the taxi to get my bag out of the trunk—I was careful to

see that he got out, too, to open the trunk—and I handed him the 10,000 Won

bill, I “knew” he would not give me change, so I just waved him on and let

him drive off laughing that he had gotten a 2100 Won tip. But the joke was really on him, because that

10,000 Won bill was nothing to me—it’s worth ¥2000 for the 25 minute trip. This was the

first country I had ever visited in which I really felt rich compared to the local folk.

The Crown Hotel had gone up a notch since my stay in Seoul a few years before (you can read my harrowing account here), and

so I went over to the Kukje Hotel. The

room was almost as much as my plane ticket (in Won) but I wanted a good night’s

sleep and a good bathroom to use before I returned to Japan. I went out for dinner, looking around the

neighborhood, obviously catering to Japanese businessmen by the number of

“Japanese” restaurants. I settled

for the “western” restaurant in the hotel itself—had the place all to myself

until dessert—and had a sirloin steak, which wasn't too bad, and cheap in Won. I then had my good

night’s sleep and in the morning caught another taxi to the airport—this time,

no tunnel and only 5500 Won.I was two hours early and so I finished writing my last three postcards, and bought stamps at the post office in the terminal. I changed back my last Won, saving 6000 for the airport tax. There was initially some trouble when I produced my Asiana Airlines ticket bought in Ulsan for the attendant, but she returned and continued business as usual. I think the problem was that I bought it at the airline’s office in Ulsan—and they didn't have an office in Ulsan, but evidently it was recently opened. It worked, anyway, and the ticket said “equivalent value of USD69.00” and it got me on the plane for the 30 minute flight. The soccer boys from Japan were getting on the same plane with me, too, I saw. And the same Korean ticket taker who had spoken to me in English conversed with them in Japanese as she directed them through the Immigration and Customs gates. On the flight we had a sandwich lunch, which was more than was served on the flight to Pusan on KAL.

From Fukuoka, despite still hampered with cold germs, I took a detour down to Saga, my old stomping grounds where I previously had lived for two years and taught English at the city's nine middle schools. Then I continued back to my home in Okayama.

---------------------------------------------------------------------

11 April 2015

Land of the Morning Calm part 2

It's springtime now and a young man's thoughts turn to fresh air and new blossoms. I'm currently revising a novel set mostly in Japan, and set mostly in springtime, but I am recalling a springtime trip I took to Korea while I was living in Japan and teaching English there. Close enough?

You can read Part 1 here.

As you may recall from Part 1, I had the best laid plans for an enjoyable spring break trip to South Korea but awoke my first morning there with a full-blown cold!

As

it turned out, it was good that I didn’t have a heavy sightseeing schedule

lined up that day. It gave me time to get my cold under control. After 12, I

went out to get something to eat. Eun-Sook, my college friend's sister who was

acting as my guide, and I had arranged to meet the following day in front of

the Koreana Hotel, the city’s largest, to catch the bus to Kyong-ju. So I

decided to walk over there and see where it was—about 3 km's walk. On the way I

thought I could find a place to eat, maybe a Kentucky Fried Chicken if I was

lucky, since I'd seen a couple on the way to Ulsan.

Seeing

Ulsan in daylight, albeit a cloudy gray daylight, Korea really looked

dismal—old and dirty, broken down, out of fashion. [This was 1992.] Very

different from the Japan I had just left. But it was interesting, nevertheless.

Ulsan is a major industrial hub, home to Hyundai Industries; perhaps it was not

meant to be glitzy and exciting.

I

found the Koreana hotel and ate in their restaurant. I had what was called on

the menu “filet mignon”—an overcooked steak that was not a real Filet Mignon

and served with a smear of mustard—for 17,000 Won (¥2500/$30). I decided I had

to keep up my strength while I fought my cold, so I took it.

Feeling

better after the meal, I decided to make my way back and try to find the block

where we first got off the bus from Pusan. That was the district where all the

young people were mingling on the sidewalk. From the bus I had seen a large

music store there. It took me about three hours of walking—the city is very

spread out—to find it, not that I was in a big hurry.

The

sun had come out and although the wind had picked up, it was becoming a

pleasant day. The fresh air made me feel better. I got some bread from a

bakery, presumably to be my supper and breakfast, later got some mikan (like

tangerines), 5 for 1000 Won (¥700).

Then

I found the block, probably the classiest street in town, where the buildings

actually looked new and in modern style, where the well-dressed people came to

mingle, where the music shop was.

Inside, I saw the prices were ridiculously low compared to music in

Japan. Korean pop/rock singers were 3500 Won (¥700), Korean-licensed cassettes

were at 3800-5000 Won, and the imported Western labels were at 10,000 to 18,000

Won (up to about ¥3200). With a bag of music cassettes in my hand, I returned

to the inn and took more medicine and went to bed after listening to a sample

of each tape on my Walkman.

Saturday.

I slept in a little, not expecting to remeet Eun-Sook until 3 pm. I returned to

the “fashionable” street, not to buy more tapes but to eat lunch in the pizza

shop I saw there. I found that my throat was too painful to swallow. The

coughing from my chest that I was doing made my throat worse. But I had used

all of my Coricidin.

That

morning I was just interested in getting something to coat my throat. Cough

drops, at least. So I took out my Korean phrase book and found the word for

“cough lozenges” and wrote the Hangûl characters on a piece of paper and the

Roman transcription next to it. I also turned to the “doctor” section and wrote

down “sore throat.”

I

took my camera to photograph some places I’d seen the previous day—not that

they were so nice looking, just recording what I saw. I took pictures of some

traditional dresses in window displays. I passed a few pharmacies until I found

one that looked better than the others.

Inside,

a man in white lab coat was at the counter and I pulled out my piece of paper

and spoke the magic Korean words, pointing to my throat. He smiled,

understanding or just amused, then looked at my paper, reading the Hangûl I

wrote. He spoke some English and sold me a bottle of cough syrup (no lozenges

available). The package came with tiny little plastic cups—like thimbles—one for

each dose, and he explained in broken English the instructions. It was pretty good stuff—for my

throat and my cough—but it didn’t cure my cold, not that I expected it to.

Feeling better just from now owning some medicine, I continued down the long

main street of Ulsan to the pizza shop.

I

saw an Asiana Airlines office on the corner and went inside to pick up a

timetable. I asked about flights from Pusan to Fukuoka, gave the girl the date,

and found they had seats available. How much, I asked and was told it was

52,000 Won. I did a quick calculation and knew that it was less than the cost

of the ferry and less than the KAL flight I bought in Japan. Let me have it, I

was practically singing across the counter at her. A 40-minute flight was better

than a 15-hour boat ride. Especially being sick.

The

pizza was good. The family that ran the shop (snack restaurant in back, bakery

store in front) were very happy to have me as a customer. When I selected a

loaf of fresh-out-of-the-oven bread to take with me for the bus trip to

Kyong-ju, they called it even when I handed them a 10,000 Won bill—the pizza

was 7500 Won and the bread (fancy kind) was 5000 Won.

I

returned to the inn and took my new medicine, then finished packing. I took a

taxi to the Koreana hotel, the designated meeting place, settled into a

comfortable chair in the lobby with a copy of the English-language Korean

Herald newspaper and a handful of English pamphlets and maps, waiting for

Eun-Sook to arrive at 3 pm.

When

Eun-Sook arrived, we took another taxi over to the bus terminal at the opposite

end of town and caught the “local” bus for Kyong-ju--the next city to the west

from Ulsan. But we had to settle for the absolutely last seats on the bus, the

back window behind us. I was really afraid of getting car sick along with my

cold, but fortunately it was a relatively short trip, about 45 minutes. I guess

the pizza was working for me. And the blessed codeine!

In

Kyong-ju we walked to the first “Yugwan” (family-owned inn) we saw and checked

in, me in the northwest corner and Eun-Sook in the southeast corner. We seemed

to be the only guests among the dozen or so rooms. We checked in and were given

towels and water. This time the water was in a large tea kettle, as though it

was freshly boiled.

The

guy checking us in (owner?) was kind of a jerk: when we gave him the money for

two nights stay, expecting change, he said (to Eun-Sook in Korean) that since

we were checking in early (4:30 pm) he’d keep the change as the early fee. Who

else did he have to check in to his place, anyway? And what time was “regular”

check-in? We could wait until then, but...we were too tired to hassle with it.

It turned out to be a custom of the country—keeping the change.

Once

checked in, we went walking around town looking for a good place to eat,

looking for a bookstore, looking for souvenir shops. We saw many tourist

hotels—Kyong-ju was a “tourist” city, after all—and lots of signs in Roman

letters saying “Tourist Hotel” and “Korean Restaurant.”

I

was beginning to be particular about my meals now, not very impressed with the

cleanliness of everything, especially where food was served, so I suggested the

“Korean” restaurant at a fancier-looking tourist hotel. But we found that it

was closed, so the hotel doorman directed us upstairs to the “grill”—which

looked like a “nightclub”: low chairs intended for sitting back and drinking

rather than scooting up to the table for eating. I had a steak—some kind,

anyway; it was just called “steak”—which was pretty good.

I

was awakened early, however. I thought we had agreed on meeting at 8:30 for

breakfast (rolls and mikan bought the night before), but I guess Eun-Sook

misunderstood when I said I would get up at 7:30—so at 7:25 there was a knock

on the door. I looked at my watch, then answered it. Waking from a dead sleep

like that, with a full cold, it was not a good moment, but I persuaded her to

come back in 30 minutes and gave her some mikan to start eating. After I pulled

myself together, I didn’t feel too bad. The sun was shining and it seemed like

a good day for sightseeing.

Our

first stop was the huge tomb mounds of the ancient Silla kings. It’s called

Ch’ônmach’ong, or “Flying Horse” tomb because of a horse’s mud guard found in

the burial chamber showing a flying horse. It is also the largest mound in this

park. The mounds could be seen rising above the buildings of the town, and they

were so perfectly round and their slopes so smooth that they had a rather

striking appearance.

My first impression upon entering the “park” was that it did not feel like a cemetery, much less one for kings. It was peaceful and

pretty in its own way. One mound was opened to the public—literally. It had

been excavated and hollowed out, and you could walk inside. A glass wall

separated the viewing area from the burial chamber. The bones were still there,

along with the gold crown and the shield, sword, and many gold rings on the

bony fingers. A little eerie, but how often do you get to walk inside someone’s

grave?

Outside,

the cherry trees were blossoming, along with other flowers I did not know the

names of, which added to the beauty of the place. From the parking lot beside

the souvenir shops—and I looked in all of them but bought nothing but

postcards—we caught a taxi to go down to the Pulguk-sa “resort area.”

The

main attraction was one of the most famous temples of Korea, Pulguk-sa. (The sa

means “temple.”) Well, it was a Sunday

and the tour buses were busy; many people dressed in their “Sunday Best” or the

traditional dresses came just to take pictures with the temple as a backdrop.

It was a little early in the year (higher altitude up on the mountainside, of

course) for the trees to be in bloom, so my pictures were not as good as the

postcards. The areas inside the compound were better looking than the front

facade.

I

had Eun-Sook take lots of pictures of me. I learned through the course of my

trip that all temples in Korea have the same colors, especially that aqua

blue-green. I found them colorful and because we don’t have such architecture

in America, we Westerners have to take pictures of it. It

was a rather extensive temple complex and the passageways wound around and

around through the hills. I lost count how many “inner temples” there were

where people were on their hands and knees praying.

It

was about lunch time by then, and the weather was sunny and warming. We decided

to take the bus up the 13 km mountain road to see Sokkuram, a cave at the top

of the mountain with a carved stone Buddha in it. The other option was to take

the 3 km straight hike up the mountainside from near Pulguk-sa, a journey that

I did not feel up to with my cold. But we had an hour to wait for the bus, so

we decided to get lunch in the “village” of souvenir shops and cafes across the

road from the Pulguk-sa parking lot.

We

had barely stepped onto the curb when old ladies were running up to us trying

to drag us into each of their own cafes, fighting for our business. Eun-Sook

decided on one and we went in. The usual kind of dinner was served: all of the

little bowls of things edible and inedible, though always interesting looking.

It was fast and cheap, anyway. The restaurateur seemed offended when we asked

for separate bowls for the soup, since I had a cold—otherwise, Korean style is

everyone helps themselves from any of the dishes.

Then

we got on the bus bound for Sokkuram, the name of the mountain which rises

behind Pulguk-sa. The road winds and winds and from high up in the bus, we can

really get a good view of the way the bus would go down to the valley below if

it were to swing a little too wide on one of those hairpin turns! Thankfully,

we arrived at the top, but not at the grotto. That was still a 2 km walk along

a wide path which wound around the mountainside.

It

was scenic as we walked. Below the trail was a river

valley. Once we arrived

at the sacred grotto,” we had to fight the crowds of people. It is an active,

holy place, where a glass wall separated the statue from the worshipers,

leaving a space of about eight feet between the glass wall and the back cave

wall, and with people in front bowing down on all fours, it was rather

crowded. There were signs saying no

photographs, but it was too dark anyway, and with people jostling me there was

no way I could take a long exposure picture.

Next,

we took the bus down the mountain and then caught a taxi in the parking lot and

rode about 15 minutes back toward Kyong-ju but got out at Anapchi Palace

grounds. This place was formerly the grounds of a huge palace of the Silla

kings, but not their real palace; no, this place was just used for summer

parties. The forest and the lake were stocked with wildlife and the three

pavilions you still see standing were originally only minor porticoes from

which to view the lake. All of the grassy areas were where the palace

stood. In one of the pavilions there was a scale model of the original palace.

Across

the street was the Kyong-ju National Museum, and we went around through it.

Unfortunately, only about 25% of the displays had English signs with them, so I spent about 15 minutes

sitting on a centrally located bench and observing the artifacts from that

short distance, then took a quick walk passed them up close. Walking out to the

exit, we saw the bus stop and waited about two minutes for the bus to arrive,

then rode it through the town of Kyong-ju until it arrived at the bus terminal,

the one two blocks from our “Yugwan” inn. We took a rest, then went looking for

a better place for dinner than we had previously.

We

found a restaurant specializing in Bulgogi, one of the dishes I can eat, which

is a kind of spicy beef stew. It was a small family-run shop near the bus

terminal, but it was clean, and on the TV in the dining area they were showing

Doogie Howser, M.D., an episode I had seen before. But what was funny was the

voices they gave the characters. You and I know they are just teenagers and

Doogie and Vinnie have higher-pitched kid voices, but in Korean you would think

they were 40-year-old men, yet their girlfriends in the program were given such

itsy-bitsy cutesy voices you would think they were five years old. Oh, well...a

bit of home far away from home. The bulgogi was delicious and I felt I had

finally come to appreciate Korean cuisine.

I

bought some mikan oranges, some chocolate, and a large bottle of soda for my

long bus trip the next day, then we retired. I would be continuing on across

the Korean peninsula to meet a pen-pal while Eun-Sook would return to Ulsan.

The next morning, Eun-Sook saw me off at the bus terminal, to make sure I got

on the right one. I had finished my Ulsan cough syrup the night before, so when

I saw the sign of ‘Pharmacy’ in English letters in the bus terminal, I went to

the counter and bought another bottle of the syrup. Good stuff.

The

bus came on time and left on time, only about one third full, so I could stretch out. But when it pulled out of the terminal, it turned left instead of

right and I panicked that it was somehow the wrong bus, but then it turned

right at the next big boulevard and headed south to the expressway. At the

tollgate, however, the bus driver was told to pull over, and I wondered if it

was some kind of random search for drugs or whatever. No, after ten minutes, a

Korean fellow climbed on board and retrieved a bag he had left on the bus. The

bus driver was angry at the delay and it was obvious as we pulled onto the

expressway that he wanted to make up for the lost time.